Editor’s note: This is a guest post by editorial professional Suzy Bills.

As a freelance editor, have you ever been confused about which pricing method to use? Does your stomach knot up when you try to decide how much to charge for a project? Have you preemptively lowered a project fee because you feared that a potential client would think your fee was too high?

If you answered yes to any of these questions, you’re not alone. You likely love the actual editing work but would prefer to avoid the whole pricing aspect of being a freelance editor.

You might never come to enjoy the pricing component of freelance editing, but the information in this article will help you gain confidence in your pricing decisions—and might also help you earn more money. So, let’s get started!

Get a 30% discount on the book

Go to www.ucpress.edu/9780520381339, under Buying Options select UC Press, and enter the coupon code 21W2240 at checkout.

Determining How Much to Charge

In the pricing process, the first step is to determine what to charge. You should base the decision on two main factors:

- How much money you need to earn to cover your monthly living expenses and to meet your savings goals

- The prices that are typical for your niches (e.g., genres and types of editing)

Let’s dive into what each factor involves.

Living Expenses

Let’s determine your living expenses – how much money you need to break even each year.

Start by determining what your average yearly expenses are. To do so, there are some steps to take.

- Add up your monthly expenses—housing, food, entertainment, and so forth—for the last 12 months. (Alternatively, calculate the average of several months, and then multiply the average by 12. If your expenses vary significantly during the year, such as because of varying heating or cooling costs, then make sure to include the high and low months when calculating the average.)

- Next, add the costs that come up only once or a few times per year, such as gifts and subscription renewals. You’ll also want to add the amounts you set aside for emergency and general savings, taxes, and retirement.

- This is the minimum amount that you need to earn annually to meet your financial needs. For our purposes, let’s say the number is $50,000.

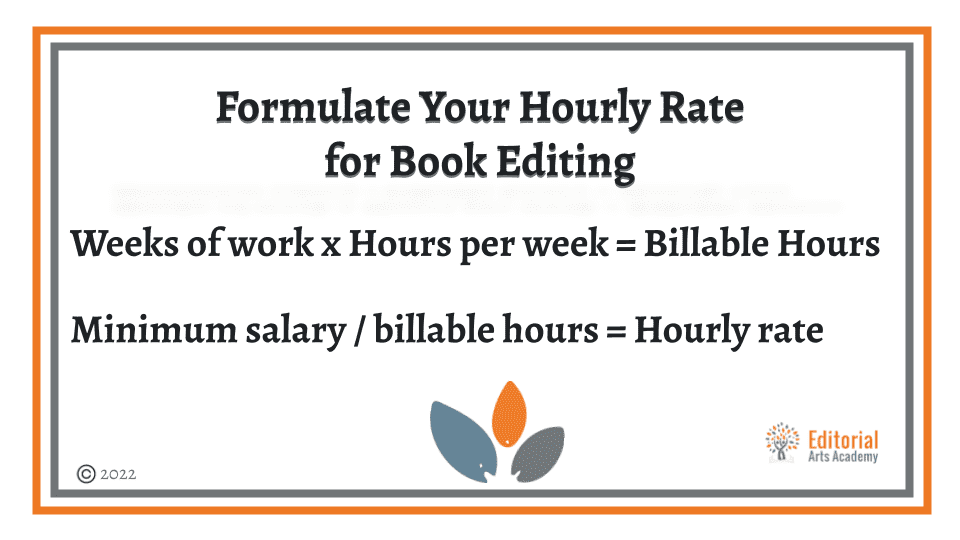

Now it’s time to figure out the number of billable hours you’ll work each week and how many vacation days, holidays, and sick days you plan to take during the year. Make sure to be realistic; for example, if family members or friends won’t be working on a holiday, you won’t want to either, so don’t plan to schedule work for that day.

- Let’s say that you can realistically work 30 billable hours a week and want 6 vacation days, 9 holidays, and 5 sick days—20 days total. That means you’ll be working 48 weeks during the year.

- Next, multiply the number of weeks (48) by the number of hours you’ll work each week (30) to arrive at the number of billable hours you’ll work during the year (1,440).

- Now, divide your average yearly expenses by the number of billable hours per year ($50,000 ÷ 1,440).

The resulting number ($34.72) is the amount you need to earn per hour in order to meet your financial needs during the year.

Going Rates in Your Niches

As a freelance editor, you get to choose how much you charge per hour. However, it’s important to understand that rates do tend to differ based on genre and type of editing. For example, publishers typically pay freelance editors less than do tech companies, and many companies pay proofreaders less than copy editors. You can find exceptions to the general trends, but if you want to mainly freelance for book publishers and indie authors, then prepare to earn less per hour than a freelance editor who works for tech and medical companies.

If you’re just starting out as a freelancer or are moving into a new genre or type of editing, how do you figure out what the going rates are? You have a few options:

- You can look at rate charts, such as the one the Editorial Freelancers Association created, keeping in mind that the rates listed aren’t hard-and-fast rules to live by.

- You can also join editing forums, such as the Facebook groups Business + Professional Development for Editors and Editors’ Association of Earth, and search for past discussions on pricing. If you don’t find a discussion regarding rates in a specific genre or for a specific editing service, you can start a new discussion about rates. (Just make sure you’ve already reviewed at least one rate chart, have searched previous posts, and have calculated what your minimum hourly fee needs to be—editors in these forums are friendly and helpful but expect posters to have already put in some work to find answers to their questions.

- Also, if you’ve already completed some research and know your minimum hourly rate, you will be able to ask a more targeted question and will get more helpful feedback.)

You’ll also benefit from testing out different hourly rates when sending price quotes to potential clients. If you’re getting a lot of project requests and not any pushback on your price quotes, then it’s probably time to increase the amount you’re charging. Simply use a higher rate when creating your next price quote, and see how the potential client responds. Keep testing out higher rates until you get a better idea of what your target market will bear.

You may find that you’re not able to earn your required minimum hourly rate because of your niches or because you’re still developing your editing skills. What then?

You might need to:

- reduce your expenses,

- work more hours per week, or

- accept projects that are in higher-paying genres or that require different editing services.

With some thought, you’ll likely be able to find the right combination, allowing you to meet your financial needs and enjoy your work, even if, for example, you won’t be accepting projects only in your favorite genre.

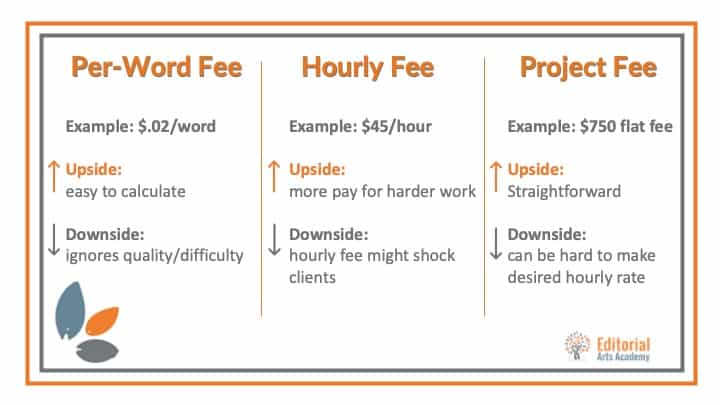

Choosing a Pricing Method

Another essential aspect of the pricing process is deciding which pricing method to use. Most freelancers use one of three methods: (1) a per-word fee, (2) an hourly fee, or (3) a project fee. Each has its strengths and weaknesses, so let’s take a look at each.

1. Per-Word Fee

When using a per-word fee, you look at the document’s word count and then multiply that number by your per-word rate to arrive at the total fee for a project. You’ll likely have different per-word rates for different types of services—for example, your per-word rate for copy editing will likely be higher than your per-word rate for proofreading since copy editing will take more time than proofreading will.

Make sure your per-word rates correlate with your required minimum hourly rate. For instance, if you estimate you can edit 2,000 words an hour and your required minimum hourly rate is $50.00, your per-word rate should be at least $0.025 per hour (i.e., $50 ÷ 2,000).

Some editors prefer this pricing method because the fee for a project is easy to calculate and they can post their per-word rates on their websites, making it easy for potential clients to determine the price for a project and whether the price is within the project budget. However, this method has some major downsides. For one, it doesn’t take into consideration the condition of the specific manuscript to be edited. If a manuscript is in really rough shape, it will take longer than average to edit, meaning you’ll be earning less per hour than you had expected. Another downside is that previously established per-word fees aren’t suitable when you need to customize your services for a client, such as if a client wants you to copy edit an article with numerous tables that need to be formatted according to a journal publisher’s specifications.

2. Hourly Fee

With an hourly fee, you establish what you want to earn per hour, and then you charge the client for the total amount of time you spend on the project. One benefit of an hourly fee is that you don’t have to determine beforehand exactly how long a project will take to complete. If it takes a little longer than expected, you won’t be making less money than you planned, because you’ll bill for the extra time.

Before you start the project you’ll still likely need to give the client an estimated time range (say, 10–12 hours), so the client has a ballpark idea of what the cost will be. As you’re editing, if you realize that you’ve significantly underestimated the time required, you’ll want to talk with the client and ask whether it’s okay to go over the estimated number of hours—you definitely don’t want to surprise the client with a bill that’s much higher than you initially estimated.

A major disadvantage of charging by the hour is that people will tend to focus less on the estimated price than on whether they think you deserve to earn the amount you’re charging per hour. You’ll likely be charging more per hour than these people make per hour as employees, and they might think your hourly rate is unreasonable. That being said, charging by the hour is the best pricing option when you’ll be working on a project that’s loosely defined, will require a lot of collaboration with the client, or isn’t limited to a certain number of words or pages. In such cases, it can be almost impossible to estimate the time required, and if the client is okay with not having a price estimate beforehand, the hourly fee method is the way to go.

3. Project Fee

When using the project-fee method, you estimate how long a project will take to complete and then you multiply that number by what you want to earn per hour. The result is your project fee, which you’ll present to the potential client rather than mentioning your hourly fee. I believe that in most cases, the project-fee method is the best pricing option.

With a project fee, you won’t have to worry about people judging whether you’re worth a certain hourly fee; instead, the deciding factor will be whether your project fee works with their budget. Clients also typically appreciate the project-fee approach because they’ll know before the start of a project exactly what the total cost will be.

Another upside of this approach is that as you increase your editing speed and efficiency, you won’t be decreasing the amount you earn on a project, as you would if you were using the hourly fee approach. Instead, you’ll be increasing what you earn per hour because you can still charge the same project fee as you would have before but you’ll be finishing faster. Additionally, with the project-fee approach, you don’t need to inform clients that you’re increasing your rates (and you should increase them at least once per year). Unless you’re increasing your rates substantially, clients likely won’t even realize that your project fees are now higher than they were in the past.

Some editors are afraid to use the project-fee approach because they’re worried that they’ll underestimate the time a project will take to finish, meaning they’ll earn less than they would have if they’d charged by the hour. True, you’ll probably underestimate sometimes, but if you’re careful when calculating the time required—and build in some extra time to account for the unexpected, which will almost always come up—you won’t run into this issue very often. Also, at other times you’ll likely overestimate the time required, and the overestimates will balance out the underestimates. Of course, if you’re spending more time on a project because the scope has increased as the project has progressed, then you need to talk with your client and explain that you’ll need to charge an additional amount to cover the increased scope.

Presenting Your Price Quote

Particularly if you’re using the hourly fee approach or the project-fee approach, you might feel nervous when presenting your cost estimate to a potential client. What if your hourly rate or project fee scares the individual away? In some cases, it probably will—and that’s okay. Your prices don’t need to fit with every potential client’s budget or expectations. However, when presenting your price quote you can apply several strategies to make potential clients more likely to accept your fees, even if they’re higher than the individuals expected.

Underlying Objectives

One of the most important strategies is to emphasize how you’ll help the individual achieve his or her underlying goal for the project. The surface-level goal might be to ensure the manuscript is clearly written and free of grammatical and punctuation errors, but the underlying goal is likely something else. For example, a novelist’s underlying goal might be for the manuscript to catch the attention of a literary agent. Make sure to uncover the underlying goal when discussing the project with the potential client.

Then, when emailing your price quote, explain how your experience and skills will enable you to help the individual achieve the underlying goal (e.g., “As a copy editor with 5 years of experience in editing YA fiction, I’ll help you polish your YA novel so literary agents won’t be distracted by typos and can instead get pulled into your story”).

Multiple Service Options

Another strategy is to present multiple service options and to list the most expensive option first.

For instance, when you review a manuscript in order to create a price quote, you might notice that the manuscript would benefit not only from fixing copy editing issues but also from increasing the flow between sentences and paragraphs. So, when presenting your price quote, include two options: copy editing and improving the flow of the document, or just copy editing the document. List the first option and its price—or a price range if you’re using the hourly fee method—and then provide a bulleted list identifying what that option will involve. (Using a bulleted list makes the items easier to scan and also emphasizes how many tasks you’ll be completing and therefore the value you’ll be providing.)

Below the first option, list the second option, its price or price range, and a bulleted list identifying the tasks you’ll be completing. By listing the higher-priced option first, you’ll be creating a benchmark that the lower-priced option will be compared to. If the first option is more expensive than the potential client expected, then the second option’s price will look more reasonable and the individual might go with that option rather than searching for a lower-priced editor. (Research indicates that sales of a product rise when the product is presented next to a more expensive option.)

Or, the individual might want the more comprehensive option and agree to the higher price, even if you think it’s higher than the potential client will agree to. (I’ve been surprised many times when a client selected my higher-priced option.)

Confidence

Additionally, be confident. Even if you’re afraid the potential client will think your quoted fees are too high, don’t let that fear come through in your email. Rather, use wording that suggests your fees are reasonable for the services and value you’ll provide.

Also convey confidence that the individual will decide to hire you. You can do so by explaining that after the individual selects an editing option, you’ll create a contract for the project. Also mention that you look forward to starting on the project. Your confidence may give a potential client the final nudge needed to move forward in hiring you for the project.

Wrapping It Up

By applying the information in this article, you’ll be on your way to effectively developing and presenting price quotes for projects. Of course, we covered only a few aspects of pricing, and you likely still have other questions, such as about when to apply a rush fee, how to overcome price objections, how to increase your rates, and which payment methods to accept.

Never fear! You can find guidance on these topics and on many other aspects of freelance editing in The Freelance Editor’s Handbook: A Complete Guide to Making Your Business Thrive. (See above for the 30% off discount code.) You’ll learn how to run a rewarding business that allows you to achieve your career goals; earn a comfortable living; and still have time for family, friends, and personal pursuits. Best of luck in your freelance editing adventure!

About Suzy Bills

Suzy Bills is an editor, an author, and a faculty member in the editing and publishing program at Brigham Young University. She was previously a lead editor for the Joseph Smith Papers, and she’s owned a writing and editing business for a decade, working with individuals and companies to publish everything from books to dissertations, video scripts, technical manuals, and marketing materials. She loves sharing her skills with others, whether through teaching, mentoring, helping authors get their thoughts on paper, or fine-tuning their writing. Her book The Freelance Editor’s Handbook was published in 2021 by the University of California Press.